Thirty-five years ago I was young. So young. I had yet to pass thirty. Yet to find a gray hair. Yet to face the limits of a mother’s love.

I was pregnant with our second child while our first, a curly-haired, single-minded miracle, was doing her best to teach me how to mother. I was an anxious and distracted student. I learned on the fly, usually only after the hard, cold fact of a mistake.

Most days I sheer-will muscled my way through the spectre of worry that haunted me like one of Dickens’ ghosts—rising up from the past, the harried present, the whisper of fears yet to come.

Our second daughter was born. She came quickly, determined to make her entrance, and within minutes decisively peed all over me. Soon thereafter I went to the movies.

It was my first outing since coming home from the hospital some weeks earlier. My sister and mother had arrived for a visit. To Steel Magnolias we must go. I virtually demanded it.

I knew enough to know it was about mothers and daughters. That someone would die. My mother knew enough to know that a postpartum mother of two little girls should perhaps choose another entertainment.

But I was young. So young.

I saw M’Lynn’s grief when Shelby died. I saw it on the screen in front of me, but that wasn’t what I felt.

Thirty-five years ago the image I carried home was of Julia Roberts unconscious, while the spaghetti bubbled on the stove, her tow headed son squalling for his mother. I was young, and this was my fear: that I would be unable to care for my children and they would be left untended. That it would be someone other than I who would shepherd them through their days.

As soon as possible, I taught them to sing the “back door” phone number to their father’s office. Pre-cell phone days, this was my emergency plan: the sing-songy, happy tune of ‘588-2300 Empire’ (yes, the carpet company commercial), set to “781-0808 Daddddyyyy”.

Such was the fortress I built around them.

Puny little fortress. Even I knew it was a house of cards.

Such was the pitiful defense I built for my heart.

I saw the shadow of fear that crossed Sally Field’s face when her beautiful adult daughter made her own life decisions. I saw her dark head bent over her daughter’s lifeless hand, her tiny shoulders curved in, toward her own breaking heart.

But she was old.

I was young. So young.

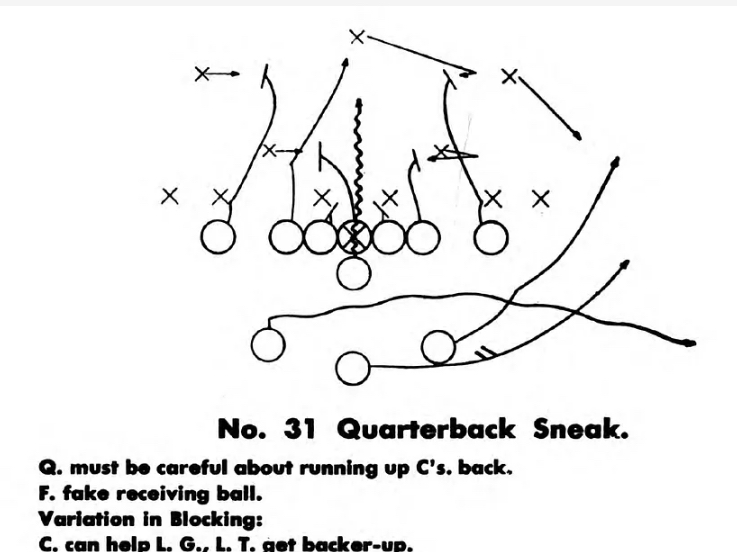

Thirty-five years ago I fancied myself a first string maternal quarterback, fleet of foot and nimble of mind. Brave enough to face any troubles the musclebound defensive line of life might pose. A juke left, a quick pivot right—I would sneak to the end zone with my heart fully intact.

Only life doesn’t work from a diagrammed plan.

Shelby’s (based on the real-life sister of writer Robert Harling) certainly hadn’t. But then, neither had her mother’s.

A fact some thirty-five years ago I managed not even to notice.

This week I went back to the movies. The same Steel Magnolias that was my postpartum distraction, only now my seat mate was that same thirty-five year old baby, expecting her own soon-to-be fourth.

I know all the jokes, the collection of brilliant actresses who meld into a seamless clutch of female friendship, the blood red armadillo cake, the impossibly perfect Sam Shepard, the all-too-believable diabetic shock.

I had seen it all before, several times since. And it still holds up, because Harling lived what he wrote. It was real, so it is real.

This time, from the first frame, I was completely locked in with M’Lynn.

Doggedly working to give Shelby the pinkly-perfect blush and bashful wedding of the century.

Waving goodbye with a smile on her lips, the raucous celebration of friends and family surrounding her, but with the ever-present mother’s furrow on her brow.

Watching her daughter build a life that is hard, sometimes so very hard, but so beautiful.

Cracking egg after egg after egg as the fear rises in her breast.

Alone, running down a hospital hall, her heels clacking out the staccato beat of “I’m coming! I’m coming! I’m coming!”

Then finally, surrounded by her sister friends, these women who have stood beside her and held her and her family all these years.

Watching these scenes for the umpteenth time I realize this:

I have never been the quarterback, reading the field and calling the plays and making miracles happen. And there’s no getting to the end zone unscathed, even if you are the quarterback.

What I’ve been is far better, because you can keep on keeping on long after the knees give out and the eyes can’t see and the helmet is gray.

I’ve been the water girl and the manager, the truck driver and the janitor, the schedule master and the bullhorn blower.

I’ve been the mom.

And the back door number, ringing straight through long after I am gone, the number set to the music of my own heart and theirs, will forever and always be exactly that:

M-O-M.